After the war, it sent battalions of middle-ranking professionals to work in London's banks, insurance companies and chartered accountancies. New Malden was - and still is- the archetypal middle-class dormitory.

Sitcom writers - probably because they lived in neighbouring Surbiton, Kingston, Teddington or Wimbledon - have regularly referenced it in British sitcoms like The Fall And Rise Of Reginald Perrin (another, Bless This House, even featured New Malden's distinct 60s-built office towers as a backdrop), largely because of it's typification of English suburbia. All that aside, New Malden's greatest claim to fame today is that it is home to Europe's largest Korean community (clearly famous residents like Jimmy Tarbuck, Gyles Brandreth and, apparently, Avengers goddess Diana Rigg, don't even register on the geographic scale of notability).

Amongst New Malden's ex-residents are yours truly and, though humbly mentioned in the same sentence, Steven Wilson, all-round über talent and front man of progressive rock giants Porcupine Tree. Steven lived in New Malden until the age of six. I know this because his house backed on to mine and we pretty much played together every single day until he moved to Hertfordshire.

There is one other notable ex-resident: Iain David McGeachy. It's highly unlikely you'll have heard of him and, sadly, it's almost as unlikely you'll have heard of John Martyn, whom McGeachy became at the outset of an acclaimed career as one of Britain's finest and most under-rated singer-songwriters. Martyn's final album, Heaven And Earth has been posthumously released this week, almost two-and-a-half years after his premature, but somewhat expected, demise at the age of 60.

Martyn was as complex as some of his music simple: growing out of the mid-60s London folk scene where he - along with Ralph McTell and Gerry Rafferty, together with a young Billy Connolly (then members of The Humblebums) - frequented a Soho music club known as 'Les Cousins'. At the time they thought they were plying their trade at a club owned by a local bloke called Les Cousins - until they discovered it was actually a pluralised French noun.

John Martyn was born in New Malden on September 11, 1948, to light opera-singing parents. When they divorced Martyn moved to Glasgow, where he grew up with his father, only occasionally returning south to spend summers with his mother on her houseboat in Kingston. As a result, Martyn would, in later life, flip effortlessly between speaking in a near-incomprehensible Glaswegian brogue and broad Mockney 'geezah'. Critics suggested a mild form of schizophrenia bordering on fraudulence, but for Martyn it was simply how he engaged the world.

|

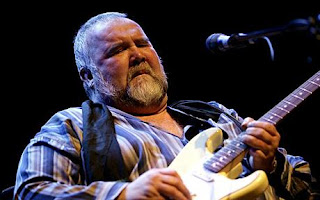

| Picture courtesy of the Daily Telegraph |

Martyn was a hellraiser: his booze-sodden and drug-fuelled touring antics with bassist Danny Thompson were legendary. Many a Martyn punter has stories of seeing him falling off the stage, drunk, or bumping into him at the bar of an adjacent pub minutes before he'd be due on stage. Such antics often overshadowed Martyn's tremendous writing and performing talent. His musical apprenticeship in Glasgow and London's folk scene helped him develop an amazing guitar technique which found it's strength in performances with his Martin acoustic famously looped through an Echoplex box to create woozy soundscapes which matched his trademark vocal style.

Martyn died from pneumonia on January 29, 2009 aged 60 and not long after receiving an OBE, arguably for being Britain's best-kept musical secret (something he actually preferred, although his 1982 album title Well Kept Secret may have taken a sly dig at the lack of commercial success his creative direction at the time was providing).

He'd been working on Heaven And Earth after what would be best described as a challenging period in anyone's life. Four years before he'd had his right leg amputated just below the knee, bizarrely, the result of a burst cyst, rather than anything more expectedly associated with his lifestyle.

Regardless, he continued to tour and showed no signs of giving up his blend of blues, jazz and folk-influenced songwriting, as Heaven And Earth testifies. It will hardly rank amongst his best albums, but then the likes of Solid Air (whose title track was written about Martyn's troubled friend Nick Drake), One World and Grace And Danger are so peerless that anything would compare badly.

Posthumous releases can be macabre cash-ins; John Martyn's catalogue has its fair share of poor quality fan-fleecing compilations released by the myriad record companies he was signed to over 41 years. But Heaven And Earth is a beautiful, if whisky-soured finale.

Quite rightly installed by The Sunday Times as album of the week, Martyn's swansong spans his love of jazz and the blues, with his signature slurred vocal giving each track a honeyed tone unlike no other musician I can think of. It takes one last, satisfying drink from the well, bringing closure on the checkered life and checkered career of one of the most gifted singer-songwriters of his generation. And certainly of the town he was born in.

No comments:

Post a Comment