Apologies if this is an overshare, but I have just emerged from one of my preferred indulgences, marinating in the bath for an hour or so reading The Word.

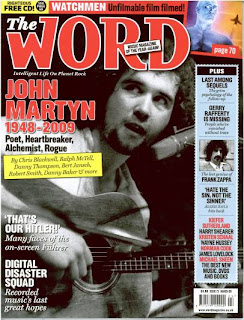

This practice must, alas, now come to an end. This is not because someone is waiting to use the bathroom, nor have I developed a prune-like complexion, but because The Word - without doubt the best cover-to-cover magazine read of the last decade - has ceased to be. Tragedy.

Co-founded by Mark Ellen and David Hepworth, veterans of the music magazine industry (Smash Hits, Q, MOJO, et al) and sometime Whistle Test and Live Aid presenters, The Word set out to be more than just another monthly for those over-30s who still actually buy CDs.

"We want to marry the New Yorker and Entertainment Weekly," Hepworth told The Observer prior to its launch in 2003. "Our target is men who know where their nearest bookshop is." As opposed to their local betting shop, one had to have assumed at the time.

The Word managed to be blokey, rather than laddish (there was plenty of that around with Loaded and FHM), knowing, rather than just knowledgeable, and literate, rather than literal. It catered for the urban Nick Hornby fan, someone who cared about the minutiae of owning an entire shelf of Robyn Hitchcock albums and had the appetite to read a seamlessly lengthy treatise on the same.

With Q - launched just as my first magazine, LM was struggling to get off the ground - Ellen and Hepworth successfully imported the irreverence of Smash Hits, shedding items such as the sock preferences of Morten Harket and the hair product advice from We've Got a Fuzzbox and We're Gonna Use It, in favour of drawing attention to the emergent CD artists of the mid-80s. Ellen and Hepworth successfully created an adult brand in music and entertainment reading, catering for music-consuming and salaried 18-34-year-olds coveted by advertisers and record labels alike. With the later MOJO, a certain reverence was applied, providing a monthly landing for musos who would have, in their youth, devoured every last inch of newsprint in the NME and Melody Maker, who wanted the latest and the oldest, and harboured strong opinions about Bob Dylan, Hot Chip and Radiohead in equal measure.

The Word addressed a different reader. Older and wiser but not without a sense of the frivolous, he (and The Word reader was largely of the male of the species) had been identified early on as '50-Quid Bloke'. "He's the guy we've all seen in Borders or HMV on a Friday afternoon, possibly after a drink or two, tie slightly undone, buying two CDs, a DVD and maybe a book – 50 quid's worth," explained Hepworth, "and frantically computing how he's going to convince his partner that this is a really, really worthwhile investment". Yep, we've all been there.

Words were The Word's strength, a writer's magazine that blissfully didn't disappear up its own thesaurus. Its readership had mortgages, children, personal computers and a yearning for something digestibly readable that they could call their own, that understood them, and that they understood. Music was it's heart, but not the only organ in its frame. Still, it could be relied upon to serve up a new angle, even on such venerable fare as The Beatles, Frank Zappa or Hendrix, artists who have been biographied to death. The Word could still find something readable to write about them. My now steam-sodden final issue contains items as diverse as The Cure's Robert Smith, a surprisingly candid interview with 'The Beatles' kid sister', Cilla Black, and a piece on the role squatting (as in illegal house tenure) has had to play in the domestic arrangements of budding rock stars.

From another angle, The Word was a random eavesdrop on the pub conversations of many of its readers. While there is certainly a chunk of its demographic who spend the vast majority of their licensed hours discussing football, there is also a sizeable group who will engage each other on the sort of topics the magazine found pertinent.

"You told us about your interests and obsessions and they were much the same as ours," Ellen wrote in his final editorial. "Old singles, bits of Anchorman, Randy Newman, The New Yorker, lying on beaches with a cold beer reading toe-curling books about the Siege of Stalingrad".

Such interests weren't confined to print, with a key aspect of The Word being the online community - The Word Massive - taking the good natured pub debates to the magazine's discussion board, a forum for citizen journalism at its most intelligent.

But progressive as this might sound, technology may also have been the cause of The Word's demise. While 50-Quid Man was its initial target but in 2012, the man who, in 2003 was indeed shelling out five Darwins for physical media, is now spending the same amount on content for their Kindle and iPad.

Like all physical forms of media, a combination of free digital competition and shrinking advertising budgets, especially by music and entertainment brands, is placing more pressure on the once mighty magazine industry. At its close, The Word had a circulation of just 25,048, down 5% on the previous year. That would be OK if you can attract big bucks advertisers, but not if the brands of conspicuous consumption are choosing GQ to flog their wares.

Some argue that The Word could have survived with a different business model. 2003's 50-Quid Man could probably have stretched to 70 or even more, despite these lean times, and could have dipped his hand deeper into his pocket for a more economically sustainable subscription. And there are those who feel that an editorial approach like The Word's would have benefited from even greater digitisation.

One such exponent of this is my good friend Ashley Norris, editor of The London Project, an iPad book celebrating London during this momentous year. "People bought The Word for two reasons," he wrote recently on The Wall social media marketing blog. "Firstly it appealed to magazine die-hards who love the feel, the design and the grammar of magazines. These people probably curse the day the web arrived and never got over the death of The Face."

Citing The Blizzard, the iPad football magazine, Norris argued that another editorial model is possible: "There is minimal design and no images – it is all about the words. I guess that The Blizzard isn’t making enough money to sustain a traditional publishing team, and it probably never will, but with an editor, freelancers and a web team on board, it has the potential to one day make some serious money."

Though The Word produced an iPad version, reading compressed PDFs of the print version's layouts didn't necessarily work, especially when the reader still craves tactility, or at least a format that holds up well in the bath.

For a seasoned magazine producer as Hepworth, producing tablet versions of magazines has a simplicity value: "Monthly magazines agonise endlessly and, in many cases, pointlessly," he wrote in the May/June issue of InPublishing, recalling the preparation of The Word's iPad edition. "In the process of adapting the content for the tablet, I had to dispense with so much of the vocabulary, so much of the furniture of the magazine, so much of the complex interplay between words and pictures. The headline and standfirst style of the average monthly magazine simply doesn't work in the new format."

"Unless they decide to go the 'bells and whistles' enhanced tablet approach," added Hepworth, "the likelihood is that the tablet is going to force all magazines to get to the point more quickly and to forsake many of the more touchy-feely aspects of the editorial craft. Personally, I won’t miss it at all."

As with any colour magazine, The Word was laid out attractively, but laid out to accomodate the writing. It was, at times, like a writer's club with a print magazine as its outlet. It showcased some of the best writing talent in the expanded universe of British music and lifestyle journalism. Features weren't inflated by picture spreads featuring reality show non-celebs in their near-altogether, but allowed journalists generous space to stretch their legs in a piece.

It cared for you if you cared about Elvis Costello as much, more, or less than Elvis Presley. Moreover, it didn't make a judgement on where you stood on such matters, and certainly didn't go out of its way to try and bring you around to its own position.

The iPad hasn't taken over just yet. I'm sure there will be some accessory manufacturer who'll come up with a waterproof tablet case, but it will never fully replace the experience of turning the pages of a magazine, especially one with the slight creep of moisture on its southern edge.

No comments:

Post a Comment