With frightening prescience, 24 hours before Gary Speed was found dead yesterday morning by his wife Louise, fellow footballer Stan Collymore wrote the following blog post:

"Suicidal thoughts.

Thankfully i've not got to that part yet,and in my last 10 years only once or twice has this practical reality entered my head,and practicality its is,unpalatable the thought may be to many.

Why a practicality? Well,if your mind is empty,your brain ceases to function,your body is pinned to the bed,the future is a dark room,with no light,and this is your reality,it takes a massive leap of faith to know that this time next week,life could be running again,smiling,my world big and my brain back as it should be.So what do some do? They don't take the leap of faith,they address a practical problem with a practical solution to them,and that is taking their own life.And sadly,too many take that route out of this hell."Collymore - much pilloried for his sexual demons - had to endure even more mockery from his own manager when he announced, 12 years ago, that he suffered from depression: "How can you be depressed when you're on £20,000 a week?", was the apparent voice of support.

The trouble is depression is far too often dismissed in much the same way, especially for men. "Get a grip", they are told. It is a tragic fact in its own right that, while women are statistically more likely to seek treatment for depression, men are more than three times as likely to take their own lives, often for a condition only they know they are dealing with.

We may never know, nor should we want to know what it was that took Gary Speed to take his own life. What we can know was that, at 42 and with an exemplary playing career behind him, a promising managerial career unfolding before him, a beautiful wife, two healthy teenage sons, and the requisite footballer's comfortable lifestyle, he was - on the outside at least - an unlikely candidate to commit suicide.

Even on Saturday - shortly before he died - Speed had appeared on the BBC's Football Focus as a studio pundit, demonstrating his solid knowledgeability of the game alongside former Leeds United teammate Gary McAllister.

Dan Walker, the show's host, spent a few hours with Speed throughout the day and, amongst all the many comments posted online about the Welshman's suicide some hours later, had as much reason as any to be shocked by what happened.

"After Focus we recorded a 10-minute piece with Gary talking about Wales' qualifying campaign for the next World Cup," Walker wrote on his BBC blog. "He spoke with passion about the fixtures and desire to see success. His hope was that the upturn in form would see his team playing in front of full stadia again. He joked about Team GB and how Scotland would be an easy game, McAllister giggled. Those words and hopes for the future seem so poignant now. There was certainly no hint of any troubles or any indication of what was going to happen a few hours later."

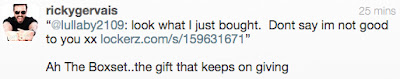

As is the modern way when tragedy strikes, Twitter becomes, perhaps, an over-inflated barometer of grief. The avalanche of tributes tweeted yesterday came from across the worlds of sport, showbusiness stars and even politics.

Few of the posts reflected any deep personal relationship with Gary Speed, but the volume of largely unqualified sentiment reflected the utter shock of news that a young football manager, who seemingly had everything going for him, could choose to exit this world so suddenly.

The sight of Aston Villa goalkeeper Shay Given, a close friend and former teammate of Speed's, unable to compose himself before his match yesterday against Swansea City, summed up the genuine, wrenching disbelief that was felt across football.

In fact, not just football. The vast majority of tributes commented on Speed's professionalism and the bewilderment over what had happened, highlighting the apparent contentment of his life, his lifestyle and his career.

Stan Collymore's earlier post underlined the fact that depression is a prison cell with few visitors. In so many people, but especially men, it goes unspoken for the very fear of mockery, of loss of respect at work, even the risk of it undermining personal relationships.

Without wishing to trivialize the condition, many mental health professionals praised the depiction of fictional Mob boss Tony Soprano's depression in The Sopranos as a pivotal story arc in the show. Dr. Glen Gabbard of Baylor College of Medicine in Texas wrote in his book The Psychology of the Sopranos: "I can't tell you how many of my colleagues have told me, that a man has come to their office seeking therapy because if a big, tough guy like Tony Soprano can get something out of it, maybe he can." The fact is, yes you can.

The tragedy, however, of Gary Speed's death reminded me of the often misquoted comment by legendary Liverpool manager Bill Shankly - "Football's not a matter of life and death, it's more important than that". In reality, Shankly used the line in a TV interview when asked about his dedication to the game: "I regret [its impact on my family] very much. Somebody said: 'Football's a matter of life and death to you'. I said, 'Listen it's more important than that.' And my family's suffered. They've been neglected."

Yesterday we learned that football is not a matter of life and death at all.