Monday, October 31, 2011

L'histoire d'amour continue

It was about this time last year I was sitting outside a Rue de Rennes cafe one crisp, autumnal Saturday morning, contemplating my then-forthcoming move to Paris. Sipping coffee and nibbling on a fresh croissant (I know "fresh" makes it sound like just-harvested mango rather than artery-hardening pastry, but...) I began writing a love letter of sorts that eventually took me forever to actually post.

The letter celebrated all the things that were drawing me to the French capital, deliciously buttery baked goods, amongst them. It took me until mid-January to actually post the thing, mainly because between that October breakfast and finding half an hour to actually do something with it, life became consumed by, well, life, and all the ups, downs and dramas that come with preparing to start a new one in another country.

There was another reason for that letter remaining 'in development' for more than two months: like any good love letter, there's always more you want to say, and either don't have the emotional vocabulary to express it, or the confidence.

It's very easy to become blasé about one's surroundings, and yet we dismiss as smug those who quit the rat-race to declare life's wonderment from a beach bar in Thailand. Paris - I can confidently say after even just ten months - has lost none of its lustre.

Perhaps it's just me: perhaps I'm just one of those people for whom childlike enthusiasm for the simplest of things doesn't wear off easily. I still hold Mr Bean-like excitement for air travel, despite being a fairly frequent air traveller for most of my professional life; the moments before a band comes on stage and strikes its opening chord are the minutes that remind me why I love live music to start with; and even after thirty years of walking up the Fulham Road on a Saturday afternoon to see Chelsea play, I'm still buzzed with the same degree of expectation I experienced the first time I visited Stamford Bridge well over 30 years ago.

So don't expect the stupid, loved-up grin to leave my face any time soon. A year ago my commute to work involved a gruesome two-hour train ride terminating in a town I would always have struggled to come to love. Now, I have a ten-minute ride by rented Vélib bicycle which takes me across the majestic Pont d’Iena, the Eiffel Tower rising before me like some colossal alien astride the Champs de Mars.

Gustave Eiffel's seventh wonder is a constant companion throughout my Parisian day: it towers over my office and then, as I fall asleep at night, it is there, less than a mile from my bedroom window, it's mad LED strobes glittering away every hour, on the hour like a Christmas tree on speed.

The tower's searchlight beam may scan the night sky like The Eye of Sauron in The Lord of the Rings, but the sweep of its light provides Paris with a fulcrum of reassurance, a giant iron guardian standing over a city of intoxicating, almost excessive beauty. It is this which enables Paris to combine the normality of daily urban living with an ethereal, dreamlike experience whenever you venture out into its streets. No wonder poets, writers, dictators and romantics have fallen under its spell. And me.

Sunday, October 30, 2011

Memories from the bottom of the garden

The Daily Mail is the self-appointed beating heart of Middle England. Much of its 'news' coverage is enraged thundering about BBC excess, or gratuitious photographs of female celebrities dressed in such a way as to leave "little to the imagination".

The Mail's other stock-in-trade is reunion stories. These come in two versions: D-Day veterans meeting up for the first time since pegging it across Juno Beach under significantly inconvenient German gunfire; and tales of childhood sweethearts who, since sharing a bus ride in 1937, have lived separate lives until a chance encounter outside a High Street pie shop ignites flames of octogenarian passion.

Thankfully, the Mail is unlikely to catch up with my own story of renewed acquaintance: it may not compete with lead-dodging Tommies for drama or Sid and Doris and their romance rekindled for warming of the heart's cockles, but it does roll back more years than I'm really at ease contemplating.

It starts with one of those lost evenings on Wikipedia that Eddie Izzard warns against - clicking on one blue link leads to another, and another, before you've acquired - momentarily - a small pile of trivia you have little use for and equally little chance of retaining.

One Tuesday evening two years ago in late March, I was idly touring the Wikiverse, vacantly jumping from link to link about rock stars connected to my native suburb on the London/Surrey borders. I'd long been curious about the high concentration of talent to have originated from this corner of England: Eric Clapton was born in the idyllic village of Ripley, was schooled in Surbiton and launched his career in the riverside pubs of Kingston. Paul Weller hails from Woking and, ironically, now has his HQ in Ripley; The Rolling Stones built their reputation at Richmond's Crawdaddy Club, The Who put nearby Eel Pie Island in Twickenham on the map, Rod Stewart was discovered busking at Twickenham railway station, and The Yardbirds shared a house in Kew. And, as What Would David Bowie Do? has previously noted, John Martyn was born in my birthtown, New Malden.

The last blue link I selected that evening revealed that, on November 3, 1967, the Royal Borough of Kingston-upon-Thames gained a new resident, Steven Wilson, lead singer, guitarist, principal songwriter and Grammy-nominated producer of Porcupine Tree, prolific collaborator of a restless number of side-projects including the highly acclaimed Blackfield with Israeli superstar Aviv Geffen, and more recently, taking on the task of remastering the entire King Crimson back catalogue.

Whether by fate or happy accident, some months before a colleague had recommended a listen to Porcupine Tree. I'd missed their emergence in the early 1990s - it happens - but dove in and acquired their albums Deadwing and In Absentia, discovering in the process a band that was regulalrly selling out legendary venues like New York's Radio City Music Hall and the Royal Albert Hall.

Although described as 'progressive rock' - by no means a derogatory description in my book - it was clear that Porcupine Tree's roots, ho-ho, lay in a rich foundation of influences, ranging from late ’60s psychedelia, early ’70s prog, ’80s metal and the more recent ambient/alt-rock scenes. Sitting, comfortably, somewhere between Muse, Athlete, Eno, Radiohead and TalkTalk, amongst other more extreme sources (German industrial rock is a strong possibility), it was a delight to hear an English band revelling in the musical territory I'd been enjoying since first taking interest in the fact I was taking interest in music itself.

So, back to my Wiki-clicking: the Steven Wilson of Porcupine Tree fame was the Steven Wilson born eight days before I arrived in the same borough. This was odd since, for the first six years of my existence there was a Steven Wilson living around the corner from me, who was born the week before me, and thus along with me would have been doing a decent job of keeping our respective neighbours awake in those winter months of 1967 and 1968.

This could still have been a huge coincidence, but I thought the easiest way to establish the facts was to chance a "This might seem strange, but..." e-mail sent to Steven's management company. Within an hour - and with the intermediary "Stalker or legit?" from his manager - the man himself wrote back: "Yes, I'm me, and you are you." Contact made, after 36 years.

Steven and I were six when we went our separate ways. His father's work took the family to Hertfordshire which, while hardly emigration, felt that way back then. Having met at kindergarten, we became friends and would frequently play together, Steven appearing at the hole in the fence at the bottom of our garden (his house backed on to mine), me going round to his house (and once disgracing myself by tripping arse-over-tit on his mum's newly washed front step, spilling vast flagons of claret all over it in the process.

Connecting again with Steven bridged a strange chasm of distance. Facebook and its ilk age have ensured that keeping in touch with your past, with school friends and old colleagues, no longer requires the services of the Pinkertons. This, however, was different. At four, five or six years old, life lacked any greater purpose or importance than what would be the Action Man outfit your next birthday might provide.

We tend to chapterise our life history: Childhood, The Teenage Years, School, First Romance, Leaving Home, Starting Work, and so on - departments of a life lived to date, each with their own set of characters, experiences and associated memories. Steven and I, on the other hand, shared only a prologue, which made me at least realise that the passing of 36 years was an awfully long time.

Before, however, we could meet in person and wistfully recount the expiry of time, progress and, in Steven's case, extreme achievement, fate intervened for, apparently, the second time (while I was working as a music journalist several years ago, Steven had in fact tried to get in touch with me. Sadly, his letter went astray). With purpose, a ticket and a backstage pass for Porcupine Tree's Amsterdam show in October 2009, we planned to catch up properly.

Unfortunately this attempt was thwarted by the brand of officiousness that is an occupational hazard to habitual liggers, but should not come between two childhood friends getting together after three and a half decades. Armed with the aftershow 'laminate' (backstage pass by another name) Steven had generously arranged for me to have, I strode up to what turned out to be a colour-blind security guard who decided that my pink pass wasn't the same colour as the puce pass on his clipboard - which by now matched the puce complexion of my face. By the time he'd resolved the issue with someone more senior, the opportunity had been lost.

This week, 36 became 38, and Steven and I finally met in Paris. His excellent solo album, Grace Before Drowning, had brought him to the prestigious Bataclan theatre in Paris.

As with the Amsterdam show, there was something surreal about seeing him on stage. I've seen friends in bands perform before, but when the lead singer is someone you last saw at the age of six, there is little to relate to apart from the knowledge that you knew each other only as young children.

When we shook hands later it wasn't a moment of or for sentiment, nor was it meant to be. It was more a moment of novelty, like two passing acquaintances from many years before falling through the same hole in time and landing in a now empty, cavernous Parisian hall.

Although almost four decades is an awful long time to cover in the handful of minutes available - the chapters both too numerous and too irrelevant to recount - it was a moment of satisfaction.

There was also pride that someone from the furthest reaches of my past, from before any of us had formed ambitions or an idea of what they wanted out of life, apart from beoming Colonel Steve Austin, had become a talented, successful musician making the kind of music I like.

There was also the sense that, in some small way, falling through that hole in time and meeting the grown up, adult Steven, built an abstract bridge to an increasingly distant chapter in my life. One that will be filled in with greater detail I'm sure when the two of us get together for a proper natter.

Saturday, October 22, 2011

Why Apple is, for now, up in the clouds

The age of instant gratification hasn't been helped by Apple. Every time they launch a shiny new bauble, we want it now. Actually, we want it yesterday, and can't come to terms with the fact it won't be available until next week.

Steve Jobs, bless him, is to blame for this "I want it, and I want it now" mindset. The medicine shows he performed to announce his latest iElixir were always slick productions of front-of-cloth magic. Usually we were enticed by the wares he had to offer.

In June he told us: "We are demoting the PC and Mac to just be a device and moving the digital hub centre of your digital life to the cloud." This came more than ten years after he declared the Mac to be hub. That's progress for you.

The day before Jobs' death, Apple unveiled iCloud - the latest incarnation of its 'storage-in-the-sky' philosophy (predated by iTools, .Mac and MobileMe) - promising an end to the apparent frustration we experience to keep our music, videos and photos synchronised on the myriad devices we now own.

Personally I've never had a problem with keeping one set of albums on my iPhone and videos on my iPad, as I rarely - if ever - want to watch a movie on my phone, and only listen to music on the iPad when I'm sat on a plane or a train. And I'm quite happy keeping the variety of music different on both.

But when Apple finally launched iCloud, plus upgrades to iTunes and its iOS platform to accommodate it, the Apple fan community rushed like lemmings to download it all. Here the first wave of vexation wafted in, for it took - I kid you not - the entire night to download and update both the iPhone and the iPad. Furthermore, I still needed to connect these devices to a Mac to transfer the new software. This was, Apple told us patronisingly, the last time we'd need to physically hook up these devices to a computer.

Then it became apparent that most of my paid-for apps were missing on the iPhone, along with most of my recently purchased albums on iTunes. Not to worry, Apple assured us, as visiting iTunes and the App Store would enable me to download everything. Laboriously, app-by-app, album-by-album, and even song-by-song. Having spent an entire night acquiring the applications in the first place - and this via a relatively fast home Internet connection - I still needed a second evening getting back stuff that had been on my devices to start with!

This may sound like curmudgeon but the expectation of any Apple product is that it should just work. It's what has made us such slavish Apple devotees. They have a knack for making something you might not have considered important, indispensably good.

Now, I'm happy to say, it's all sorted. My initial fears about how iCloud would work when you have a storage disparity between iTunes content living on a Mac (my MacBook Air has a 128Gb hard drive which is stuffed full), and the smaller capacities of the iPhone and iPad (32Gb each), have been allayed by the fact that the much-vaunted automatic synchronisation can be controlled.

I am, though, left with the feeling that the absence of a USB cable between phone, tablet and PC is only a marginal improvement. Before, I ripped a CD, then hooked up my iPhone and there it would be, emporter, as the French might say. Now I need WiFi. Something presumptuous there.

I still don't have a huge need to keep everything synchronized on every single Apple device I own, but perhaps that's just me and the compartmentalised manner with which I regard the iPhone, iPad and MacBook I use.

True, the photo synchronisation is a very smart aspect of iCloud: take a picture on your iPhone and it's instantly shared with your other Apple devices.

All this, however, does make the assumption that you have either access to WiFi, or an accommodating 3G mobile provider. Carriers are increasingly imposing data limits on downloads and uploads, which raises questions about how viable a ubiquitous service like iCloud will be as such economies increase. And clearly you won't want this to be active when taking pictures on holiday.

The iCloud story is not yet finished, either. To come is iTunes Match, with which for a fee, Apple will miraculously scan the iTunes library on your home computer and 'add' the same songs to your iCloud content, regardless of how this music was acquired in the first place.

On this I remain sceptical: when you have somewhere over 1000 albums on a hard drive as I do, of which some are not widely available commercially or came off the front cover of a music magazine, I doubt very much that iTunes Match will be able to find them. More worrying is that as the service is based on your paid-for storage capacity, to maintain this wonderful idea will cost $25 a year on top of the additional iCloud storage you need to buy from Apple to accommodate it - and that could cost up to $100 a year for a maximum of 55Gb more (which is not enough, clearly, for all the content I might be storing in the iCloud).

There is much to like about iCloud's intentions. It can be a minor annoyance when you download the Bombay Bicycle Club's new album to your Mac on a Saturday and forget to add it to your iPhone before heading off to work on a Monday morning. But it is only a minor annoyance.

The cloud story is not yet ready for prime time. True, relying less on huge and breakable hard drives to store your content (that's right - you own it, you paid for it) is a good idea. But, like Google's idea of running laptops on cloud-based apps, it assumes that we're always on, and always connected.

When I can't get a decent 3G signal in the centers of London and Paris, let alone find a WiFi hotspot that doesn't cost an arm and a leg for just an hour's time online, the idea of ubiquitous access to content is still somewhat far-fetched. For now at least.

Monday, October 17, 2011

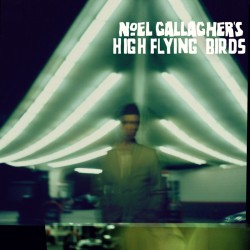

Brother Beyond

Once or twice in a generation, pop music generates a rivalry that has the press gnawing upon it until they get bored and move on. The fact that the rivalry was, probably, their creation in the first place is neither here or there, the scamps.

In the 1960s we had The Beatles and The Stones; 20 years later, it was Duran Duran in a battle of hairspray with Spandau Ballet. They were followed after the intermission by Simple Minds and U2, a bout clearly won by the latter who went on to meet Coldplay in an exchange of ideas about fair trade coffee.

Thankfully, with the exception of Tupac and Notorious B.I.G., few have ever turned really nasty (although there were rumours of an ugly backstage spat between Mozart and that pipsqueak Beethoven at Glasto '90. 1790.)

It is, though, unusual that a member of pop's great firmament should find themselves absorbed by not one but two rivalries in the course of their career. Lily Allen came close by issuing the pop princess equivalent of the closing time "come on then!" to Courtney Love and Katy Perry, but to my knowledge, only Noel Gallagher has been embroiled in a full-on, no-holds-barred rock'n'roll dust-up twice.

The first came to a head on August 14, 1995 when, through either disruptive thinking or unbelievable stupidity, Blur's Country House was released on the same day as Oasis appropriately brought out Roll With It. Being the height of the silly season the event was marked by being the lead story on a host of organisations customarily indifferent to such triviality. It even made the BBC’s 10 O'Clock News, with summer stand-in presenter John Humphries harrumphing with unease as he introduced that evening's 'fancy that?' piece on the affair.

Planted, not particularly deeply, within the Blur-Oasis rough-and-tumble was the British class obsession: Blur's lower/upper-middle class art college background was pitched into the contretemps, with Oasis - hailing from Manchester's hardened streets - a journalistic gift. For a year or so it made for mildy amusing copy, but the true outcome of the handbags between Blur and Oasis (which saw Liam Gallagher turning his wannabe school playground bully persona up to 11) was to mask the simmering sibling rivalry within Oasis itself.

Part of me wishes it had ended like that. It would’ve made a great headline: ‘Plum throws plum'.

The sparring between the brothers Gallagher maintained the band's reputation from the moment they first emerged in the early 90s until its bitter end in 2009. For a while you could be forgiven for thinking it was part of their schtick.

Fast-forwarding through more than a decade-and-a-half of simmering fraternal discord, the eventual separation of Noel and Liam Gallagher, the spiritual heart of Oasis, came as no surprise to anyone. The denouement unfolded backstage at the Rock en Seine festival in Paris when a row about the junior Gallagher's Pretty Green clothing label led to him threatening his elder brother with, first a guitar, and then a piece of fruit.

"On the way out he picked up a plum and threw it across the dressing room and it smashed against the wall," Gallagher Senior recounted at a press conference last July to announce his debut solo album, Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds. "Part of me wishes it had ended like that. It would’ve made a great headline: ‘Plum throws plum',"

Musically, neither Gallagher has moved on with their respective projects. Beady Eye's Different Gear, Still Speeding and ...High Flying Birds could easily have been named Oasis: What Happened Next. Both Gallaghers remain rooted in the Beatles/Kinks/Steve Marriott-60s-vibe-with-psychadelic-hints that became the stock-in-trade of Oasis, and continues to be Paul Weller's muse to this day.

Solo albums invariably represent freedom and a chance to explore music that wouldn't have worked, or been accepted in a group environment. Some are pure self indulgence, some offer a cathartic release valve.

Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds is neither indulgent or cathartic as it's perfectly clear the 44-year-old Gallagher really couldn't care less about what anyone, least of all his brother, thinks of him. It might not offer any dramatic directional surprises, but it is certainly the album of a supreme and natural songwriter, confidently enjoying his job.

Scanning the track listing, titles such as The Death Of You And Me and If I Had A Gun might fool the lazy journalist into thinking this is an album about Our Kid. It isn't. The Death Of You And Me, the album's first single release, is a Ray Davies-esque jaunt which includes a riotously carefree New Orleans trad jazz accompaniment created, apparently, by the various members of the production team impersonating brass instruments.

If I Had A Gun is just an unashamed love song built around Gallagher's favourite F#m7 chord (think Wonderwall, viewers) and more Mellotron and grungy Gibson to keep things from getting too sloppy. The happy-go-lucky, hippy-dippy 60s sentiment continues with Dream On, picking up the Oasis template for such throwback fluff with a song Gallagher himself brands "pop for pop's sake - a tune so good maybe people won't listen to the words".

Where Gallagher does let loose with his creative spirit, and shakes off his clear affection for The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society, you get something that would make you put down the dishmop. AKA...What A Life! is such a track. With its chugging piano rhythm - reminiscent of Al Stewart's On The Border, or perhaps On The Border covered by the Scissor Sisters - it pounds along with a thudding big sound that defies the fact it was recorded by Gallagher in a tiny studio with the teaboy providing the piano sample (fact).

In the olden days, a great album was marked by a bold opening track, something intriguing to end Side 1 and keep up interest to turn over, a lively commencement to Side 2, and a memorable closer with, ideally, a lengthy guitar solo to take you into the album's outro. Stop The Clocks has that. Written by Gallagher ten years ago while in Thailand, had it have been recorded then it may have been just another Champagne Supernova. Without the Manchester scally act, it takes on a much more interesting dynamic, as rich and as curious as anything on Paul Weller's 22 Dreams, layered with more prog-ish coatings of Mellotron, acoustic guitar and organ, and closing with a storming piece of guitar work from Paul 'Strangeboy' Stacey, a former Oasis session player who brings Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds to an end with fretwork that would leave the sky black with hats if it had Johnny Greenwood's name attached to it.

Noel Gallagher is, by his own admission, neither a great guitarist nor a gifted technical musician, but he gives what you and I want, sometimes, more than anything else in a record - a good time. Something to make the morning commute more bearable, something to tune the world out, to make washing up or other household chores pass by with vim, vigour and other brands of household cleaning products.

While ...High Flying Birds will never be a solo album to have the world shouting, in unison, "I never knew he had that in him", for all its resolute rooting in territory Oasis rarely - if ever - strayed from, it reeks of unbridled enjoyment. That of its originator, as well as that of us listeners.

Labels:

Blur,

Coldplay,

Duran Duran,

Lily Allen,

Noel Gallagher,

Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds,

Notorious B.I.G.,

Oasis,

plums,

Simple Minds,

Spandau Ballet,

The Beatles,

the Rolling Stones,

Tupac,

U2

Sunday, October 16, 2011

Skirting the RIM of Hell

Hello everyone. My name is Simon, and I used to be an addict.

I was using morning, noon and night. It was the first thing I needed when I woke, last thing I did before I went to bed. Sometimes I didn't go to bed at all, and continued through the night.

However, I sought help and sorted myself out, and that's why I'm here today to tell the story. I successfully rejected part of my life that was spiraling out of control with, frankly, only one outcome.

It is now ten months since I gave up my BlackBerry.

Today I'm completely clean. True, I have an iPhone, which sort of works as a phone and has all the non-phone things you expect these days. From a phone, of course. And although they say the first 100 days of sobriety are the hardest, these last ten months of abstinence have been relatively easy.

For a start, I no longer panic at the sight of a little red LED winking at me; I don't suffer spikes in blood pressure caused by the clanging chime of doom that annnounces a new missive; and my spine is returning to normal curviture, as I am no longer finding myself hunched over like an early 1970s prog rock guitarist.

That said, switching to methodone - sorry, iPhone - hasn't been without its side effects. Syntax, for exampled, has struggled, with coherence occasionally varying wildly.

E-mails to important people (you know, bosses, CEOs) have been hampered by words like "of" and "on" being autocorrected to "if"and "in" in the final article.

In fact this feature is so counter-productive I have terned it of and will now mayk do with my own spalling capeabillytees.

So while you congratulate my self-restraint, I have to confess that this last week I have been feeling terribly smug. Smug in a sort of German-standard-of-living smugness. Smug in a couple-posing-as-husband-and-wife-for-Sunday-colour-supplement-furniture-ad way. Smug in an "I invested well in my 20s and am now retiring in my early 50s to live in comfort and wear a lot of pastel" level of smuggery. I'll stop now with the smug references.

Because when people come to remember where they were during The Great BlackBerry Blackout I will simply recall enjoying the silence. No one was sending e-mails, so there were none to be read. Entire business meetings were conducted with near 100% attention. Train journeys became torturous events as newspapers returned to brief popularity. Conclusive, engaging conversations broke out in households. One person even walked across to my desk to ask me a question in person. In person!

People were left hurt, baffled and unable to cope (Colleague #1: "Where's the fax machine?". Colleague #2: "The what?". Colleague #1: "The fax machine!". Colleague #2: "What's that then?". Colleague #1: "Aaaaagggghhhhhh!"). Some threatened the return of Hotmail. Others took to begging in the street for just a fix, a sniff of e-mail. Just one - it didn't have to be an entire back-and-forth.

So, for a few days, people actually had to open their laptops to do some work. Engagement with others meant, for a short time at least, writing messages with thought, rather than stabbed out on a tiny QWERTY keyboard in the back of a taxi.

Ridiculous to think that BlackBerry's outtage (which, ironically, my iPhone's autocorrect thinks should be "outrage") should have been considered by many to be some sort of temporary return to Year Zero. As if being blamed for causing the UK riots wasn't bad enough, BlackBerry was now being held responsible for bringing the world of business communications to its knees during a time of worsening global financial mayhem.

Makes you wonder how on earth they coped during the great Typewriter Correction Fluid Shortage of 1981...

I was using morning, noon and night. It was the first thing I needed when I woke, last thing I did before I went to bed. Sometimes I didn't go to bed at all, and continued through the night.

However, I sought help and sorted myself out, and that's why I'm here today to tell the story. I successfully rejected part of my life that was spiraling out of control with, frankly, only one outcome.

It is now ten months since I gave up my BlackBerry.

Today I'm completely clean. True, I have an iPhone, which sort of works as a phone and has all the non-phone things you expect these days. From a phone, of course. And although they say the first 100 days of sobriety are the hardest, these last ten months of abstinence have been relatively easy.

For a start, I no longer panic at the sight of a little red LED winking at me; I don't suffer spikes in blood pressure caused by the clanging chime of doom that annnounces a new missive; and my spine is returning to normal curviture, as I am no longer finding myself hunched over like an early 1970s prog rock guitarist.

That said, switching to methodone - sorry, iPhone - hasn't been without its side effects. Syntax, for exampled, has struggled, with coherence occasionally varying wildly.

E-mails to important people (you know, bosses, CEOs) have been hampered by words like "of" and "on" being autocorrected to "if"and "in" in the final article.

In fact this feature is so counter-productive I have terned it of and will now mayk do with my own spalling capeabillytees.

So while you congratulate my self-restraint, I have to confess that this last week I have been feeling terribly smug. Smug in a sort of German-standard-of-living smugness. Smug in a couple-posing-as-husband-and-wife-for-Sunday-colour-supplement-furniture-ad way. Smug in an "I invested well in my 20s and am now retiring in my early 50s to live in comfort and wear a lot of pastel" level of smuggery. I'll stop now with the smug references.

Because when people come to remember where they were during The Great BlackBerry Blackout I will simply recall enjoying the silence. No one was sending e-mails, so there were none to be read. Entire business meetings were conducted with near 100% attention. Train journeys became torturous events as newspapers returned to brief popularity. Conclusive, engaging conversations broke out in households. One person even walked across to my desk to ask me a question in person. In person!

People were left hurt, baffled and unable to cope (Colleague #1: "Where's the fax machine?". Colleague #2: "The what?". Colleague #1: "The fax machine!". Colleague #2: "What's that then?". Colleague #1: "Aaaaagggghhhhhh!"). Some threatened the return of Hotmail. Others took to begging in the street for just a fix, a sniff of e-mail. Just one - it didn't have to be an entire back-and-forth.

So, for a few days, people actually had to open their laptops to do some work. Engagement with others meant, for a short time at least, writing messages with thought, rather than stabbed out on a tiny QWERTY keyboard in the back of a taxi.

Ridiculous to think that BlackBerry's outtage (which, ironically, my iPhone's autocorrect thinks should be "outrage") should have been considered by many to be some sort of temporary return to Year Zero. As if being blamed for causing the UK riots wasn't bad enough, BlackBerry was now being held responsible for bringing the world of business communications to its knees during a time of worsening global financial mayhem.

Makes you wonder how on earth they coped during the great Typewriter Correction Fluid Shortage of 1981...

Friday, October 14, 2011

American Dreaming - tales about the Southland

|

| Alex Demyan and NewOrleansOnline.com |

The trip - though criminally short - was nevertheless long enough to reinforce my belief that for all the exotic, fascinating and culturally diverse destinations the world has to offer, I am still drawn to - no, absorbed by - the United States, its people and its places.

A week earlier What Would David Bowie Do? had been on American soil for a business trip, and between this visit and the journey down south, spent an inordinate amount of time arriving at, passing through or departing from various US airports. It was an experience which served only to demonstrate what fascinating observatories of local life they are.

New Orleans' delightfully named Louis Armstrong International Airport (known locally as “Satchmo”) provided a perfect sample of the rich potpourri of the resident and the transitory, its waiting areas, walkways and lounges like a microcosmic fishtank sourced from the greater ocean of American life.

Amid all the usual departure gate hub-bub was a regular fixture at any US departure lounge: the Willy Loman. Conspicuously pacing up and down, feverishly pitching his wares via an apparently invisible Bluetooth headset, he appeared insanely animated in front of an indifferent audience. Next to me sat the sweet old gran heading home to visit the grandkids; across the divide, the single mum struggling with children and luggage; and - yes, fans of Airplane! - elsewhere at that departure gate was the obligatory nun. Can anyone remember the last time they saw a nun anywhere other than an airport?

I've been an annual visitor to the United States for almost 20 years, and lived there for two of them. I'm sure some will regard me as being of the barnyard for lacking breadth of horizon, that I should be spending my vacations backpacking through the Himalaya, exploring Mayan temples by kayak or in-line skating up the Ho-Chi Minh Trail. And while it's true that American travel doesn't present any greater challenge than deciding between the bewildering choice of drive-throughs and motel chains, the country isn't any less rewarding, enriching or invigorating a visit.

America has never failed to live up to expectations: my first ever visit took me to Los Angeles where - like Stevie Wonder's "hard town Mississippi" rural refugee - I couldn't help saying to myself, "Yeah, just like I pictured it".

You have to remember that I grew up in gloomy, grey 1970s Britain. LA - represented by Charlie's Angels and CHiPs - was America: a blue-skied paradise populated by big cars, perfect teeth and flawless beauty. Jaclyn Smith was her name.

I knew this was somewhere I wanted to visit, even be part of, and I eventually got my wish. Subsequently, and exhaustively, I've explored the better two-thirds of California - from San Diego to San Francisco, Venice Beach and Carmel on the coast east into and out of the deserts to the majestic Sierras, the jaw-droppingly beautiful Yosemite and the glorious tranquility of Lake Tahoe. I even know the taxi back-doubles to reach Los Angeles International Airport.

California was only the beginning: I branched into the Pacific Northwest - once known for Twin Peaks, Nirvana and Big Foot, and now, dreadfully fey vampires - coming across a bizarre mock Bavarian village in the Cascade Mountains and Greenpeace chasing Indian whale hunters around Neah Bay, the remotest tip of the 'lower 49 states'; I've been bitten to death in South Carolina and bored to death in southern Texas; I've hiked the steel canyons of Manhattan and barrelled through the sandstone canyons of Utah in a 4x4, blaring out The Clash, just in case an Osmond was lurking behind a tree. I've covered a lot of ground, but in truth I've barely scratched the surface.

The South, today, may not be as dirt-poor as it was when share croppers came in from the fields to Memphis to find their fortunes - or the sanctuary of a Beale Street juke joint - but it still struggles. Mississippi and its southern neighbour Louisiana boast the poorest communities in the United States. Downtown Memphis, in particular, is marked by its vacant storefronts, its homeless and a noticeable lethargy, even in the middle of a normal working day.

And yet this is the corner of America from which pop music as we know it today was founded. The rhythms that emerged from its cotton plantations to fuse with gospel and folk, evolving, in Darwinian fashion, into blues and jazz, became the rock and roll that established music as the predominant youth culture of the last 60 years.

At risk of committing Lennonesque blasphemy - dangerous sport when it comes to the Bible Belt - there are parallels between the South and the Holy Land. To visit the original haunts of Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Son House, BB King and Robert Johnson (the founding member of the 27 Club) carries the same sensation of walking amid mythic history as visiting Nazareth, Galilee and other places of biblical history in Israel, as I was fortunate to do last year.

Memphis is Jerusalem and Clarksdale - a long, straight, hour-long drive away down Highway 61 (yes, that Highway 61) and into Mississippi, is Bethlehem. The crossroads where Highways 61 and 49 meet is Manger Square. Here, the story goes, Robert Johnson made a deal with the Devil for the ability to play the guitar. I won't dwell on the symbolism of the crossed guitars which now marks this junction, save to say it's a dilapidated symbol at an intersection few would want to linger at.

The blues spawned by the Mississippi Delta may have eventually found its way into British bedrooms in the 1960s, where it was indulged by white, suburban middle class boys, but the region bears little benefit today of the excess and opulence it gave rise to. Apart from the Delta Blues Museum and an arts center co-founded by local resident Morgan Freeman, Clarksdale has little else. Down at that crossroads you become conscious that time has scarcely moved on in the 80 years since Johnson's apocryphal satanic encounter.

As it was for those early blues pioneers, Memphis remains the area's aspirational magnet. Beale Street today might be a theme park version of the street it once was, but amid the bachelor and bachelorette parties staggering up and down its main drag of an evening, authentic, live blues can still be heard.

BB King's, at the corner of Beale and 2nd, is now part of a franchised chain, but the Memphis original is a must-see, if only for the quality of live acts it hosts every night, but also out of homage to its patron, who does still make appearances when, at the age of 86, he has time while remarkably still touring.

King, born in share-cropping farmland 130 miles away in Indianola, Mississippi, came to Memphis as a 21-year-old and picked up guitar-playing sessions on the legendary local radio station WDIA. It was while DJing and playing blues for WDIA that he acquired the nickname 'Beale Street Blues Boy' - B.B.

He walked out with a 10-inch acetate disc of the recordings and that may well have been that. Fate - and producer Sam Philips' receptionist - brought Elvis Presley back to Sun Studios, where he recorded and released That's All Right in 1954 and sparked a global cultural phenomenon of seismic proportions.

In 1957, at the age of just 22, Presley moved in to Graceland, just nine miles south-east of where Sun Studios still stands today. The first thing that strikes you about Graceland is just how modest this cod-colonial pile is by mansion standards. Newly-minted English football players would consider it tiny. It is as much a shrine to the King of Rock'n'Roll as it is to what passed for rock star interior design in the era Presley lived in it.

Visiting it today, one sees a house frozen in time, with 70s chintz and patterns which would, today, come with a health warning. Graceland's modest size is tempered by the fact that its estate boasts a large shed full of Presley's cars - a mix of the gaudy and the opulent - as well as not one but two airliners, which used to fly under the call sign 'Hound Dog One'.

Such arriviste trappings might be incongruous to the poverty around Memphis, but Graceland is a revered local money-spinner. A lesser known local attraction is the Stax studio. Rebuilt to perfection (the original was knocked down by a property developer), it plays another important role in the cultural heritage of Memphis, celebrating both a record label and the single neighbourhood that produced Isaac Hayes, Ike Turner, Booker T. Jones, Rufus Thomas, Steve Cropper and Donald 'Duck' Dunn.

This was the multicultural backbone of Stax Records: a fusion of rhythm, soul, blues and gospel influenced which, combined, challenged the still-segregated landscape of American society in the early 1960s - in the very city where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated, outside room 306 of the Lorraine Hotel.

Today the hotel is a part of the Civil Rights Museum, a fantastically curated, chronological exhibition of a period of American history few can be proud of, and which depicts a story that spans multiple centuries to within my lifetime.

Heading south of Memphis, following the curves of the Mississippi, you encounter more of the impoverished rural landscapes people have either aspired to break away from, or reluctantly accepted to be their lot and stayed put.

Challenging this is Natchez, a Miss Havershamesque town overlooking the Mississippi as it bends between Louisiana and the state named after it. When cotton was the currency on the Mississippi - and a lucrative one at that - Natchez, with its commanding view of the river, was a wealthy town. Today, its wealth has visibly faded, although the town centre retains a fabric of suburban respectability.

Natchez is a charming town, but hardly worthy of an overnight stay. If you do, two attractions make it worthwhile. Firstly, there is the Under-the-Hill Saloon on Silver Street. This slightly creaky riverside pub, with its - how do you say this politely? - eccentric barman, Harley-riding clientele and eclectic decor (yes, that was a real hand grenade we saw behind the bar) is a local institution.

Above it is the three-room Mark Twain Guest House, to which guests share a single bathroom and, for their $100 night, do without in-room televisions and telephones in order to preserve the "somewhat historic atmosphere of our rooms".

Whether Mark Twain ever stayed there for real remains to be proven. If he had have done, he'd have certainly eaten at The Magnolia Grill next door which - either through a paucity of anything better or, simply because of the atmosphere of the evening - served up arguably the best meal of the entire week spent south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

First timers, travel writers and more seasoned visitors to the United States find it near-impossible to avoid commenting on the enormity of the country - its places and its people - or on the absurdity of its excess. And yet, in Natchez, What Would David Bowie Do? encountered perhaps the most wasteful application of a natural resource on God's green: a petrol-driven truck employed just to transport patrons less then 50 feet up and down the causeway between the entrance of a Mississippi steamer casino boat and the roadway where shuttle buses drop them off. Having picked them up from the car park further up a hill. Let me go over that again: a truck, which transports people 50 feet up or down a landing ramp.

And so on further to the mouth of the Mighty Mississip' itself, New Orleans - the final destination of this brief road trip. Simply put, one of the most charming cities on the map, even though a clearly pissed off Mother Nature did her best to wipe it clean off that map in 2005 when she sent Hurricane Katrina spinning across the Gulf of Mexico.

When she struck, Katrina breached the delicate acquaintance The Big Easy had enjoyed with the Gulf since the port was founded by the French in 1718. Flooding caused by the city's levees breaking killed more than 1000 residents and displaced tens of thousands more. In fact, exactly how many were displaced is still not known, six years later. Census figures have shown that New Orleans - once America's third-largest city - lost almost a third of its population over the last decade. Today it is America's 52nd largest city.

Built, largely, over reclaimed swampland, New Orleans is a cocktail bar's shaker of influences. With its clearly French foundation, the infusion of Creole, Haitian, Spanish and other European elements give the city a flavour unlike any other I've visited in America with, perhaps, the exception of San Francisco.

|

| Cosmo Condina/NewOrleansOnline.com |

It is loud and colourful, with no shortage of bars to tempt you in. Some even have authentic jazz and blues. Others, however, are just garish karaoke bars, catering to the culture clash of Mid-West sales reps attending conventions and Mid-West rednecks who all converge on the city at the same time.

At least it's easy to set the two crowds apart: the reps are all dressed in sports jackets, their mobile phones holstered at the hip, while the rednecks almost exclusively wearing baseball hats, facial hair and capped-sleeve T-shirts bearing logos of a motor oil brands.

New Orleans is not, of course, just one street. During the daytime, the French Quarter provides both respite from the aching sun as well as a charming and thoroughly walkable area in which to step in and out of bars for a cooling drink, or to sample some of the food delights, especially creole cooking and, for the totally indulgent, a local speciality known as a Po' Boy.

These are, essentially, very large sandwiches - what Americans will refer to as a "submarine", owing to them being made out of a French baguette, are the size of an actual submarine, and are loaded with so much unhealthy crap that they can be legitimately be described as weapons of mass destruction.

The Po' Boy originated in the Great Depression, when a pair of entrepreneurial brothers came up with the idea of selling foot-long sandwiches to poor families on the basis that each 'Poor Boy' would adequately provide a meal to an entire household. Today they are far from cheap, and given the propensity for over-indulgence, you are unlikely to see a Po' Boy eaten by either a single family, or anyone on a low income.

Here, in fact, lies a pillar of the American paradox: the United States is the world's wealthiest nation, and yet 15% of its 312 million inhabitants live below the poverty line. That's the equivalent of the entire population of Spain. America remains highly aspirational: TV advertising is about doing well, living healthier and aspiring to own that next-generation SUV, despite the fact you will not be able to afford its fuel or, come to think of it, the house to park it outside. This is a country with a gross domestic product - of almost $15 trillion, but where child poverty is twice as high as many European countries, and where more than half a million children are officially listed as homeless.

Driving through - or driving past - poverty like this makes no difference as to whether you're in the USA or the outskirts of Mumbai. Of course, it asks moral questions of the traveller, but as self-indulgent as this sounds, my curiosity for a part of America which has struggled for long enough, and will, sadly, struggle for a lot longer, is driven by a celebration of the culture and pleasure it has provided the world.

Lacking any real erudition, I'll leave more dexterous reflections on Americana in general to Kerouac and Bryson: I wouldn't even dare suggest this dog-and-pony show of mine would, in any case, offer anything deep. But for all of America's critics and cynics, who say it lacks culture, history, society, I say take a closer look. Look deeper and you will find a country that might surprise you and even enchant you in the way it did me before I'd even set foot there - and has continued enchanting me ever since. My own personal American road movie is not yet past the opening titles. There is plenty more to come.

Sunday, October 9, 2011

With strings attached

On a recent flight to the US I was scanning the choice of on-demand movies available on the vision-challenging 'state-of-the-art' seat-back TV and came across the legendary This Is Spinal Tap. Regarded as the greatest movie - fictional or factual - ever made about rock music, I'd forgotten just how damn funny it was.

Few real bands - if any - have ever refuted its accuracy and the mirror it hilariously held up to rock's splendid talent for the self-regarding and the delusional. It was - and still is - a tour bus staple. A tradition amongst music journalists, on being invited in to the rock star's abode, has been to note the copy of This Is Spinal Tap in prominent view on a shelf.

Despite its popularity, rare is the band to say: "Better not do that - too Tap." Which is why, on the release today of New Blood, Peter Gabriel's orchestral reworking of selected songs from his 37-year solo career, he may not have taken into account an interchange in the film between bassist Derek Smalls and Spinal Tap's blond lead singer, David St. Hubbins. Following the departure of guitarist Nigel Tufnell - they ruminate on the "gift of freedom":

St.Hubbins: "I've always wanted to do a collection of my acoustic numbers with the London Philharmonic, as you know." Smalls: "We're lucky. I mean people...people should be envying us." St.Hubbins: "I envy us."

Gabriel is one of music's most mercurial talents. His notoriously laborious writing process is lengthy only because, in his own words, "I'm an awkward bugger". When not endlessly tinkering with layer after layer of sound on his studio albums, he's forming human rights charities like Witness, or The Elders, the thought leadership collective of former world leaders, or he's investing in technology interests like OD2 (the online music service later sold to Nokia), the music streaming site WE7, or the recording equipment giant Solid State Logic.

So the fact that Gabriel's latest album is a consecutive release to take the orchestral route, following last year's Scratch My Back, suggests an exhaustion of new ideas. Just as MTV Unplugged gave a new lease of life to many an electrified back catalogue, the orchestral revisit has often appeared in the absence of anything new. George Michael and Sting (someone never to shy away from demonstrating his apparent eclectic prowess) have both recently toured with orchestras, with Sting also releasing an album with full orchestral accompaniment, all in the notable absence of any new studio material.

Scratch My Back wasn't Gabriel's first recorded encounter with an orchestra - his eponymous debut solo album in 1977 contained the extremely cinematic Down The Dolce Vita - but it represented a new take, "reimagining" songs, such as a paired-down version of Paul Simon's Boy In The Bubble and a dark and dramatic read of Arcade Fire's My Body Is A Cage.

New Blood is a little more conventional: like it's predecessor, Gabriel and arranger John Metcalfe replace the rock conventions of drum and guitar with the polyphonic range of a 48-piece orchestra.

But whereas Scratch My Back served up some genuine surprises, both in the choice of songs as well as their execution, New Blood - perhaps because of the familiarity borne of over three decades of listening to some of the tracks - is more of an album of, well, Peter Gabriel songs set to an orchestra.

As one of the first owners of a Fairlight CMI, the sampling keyboard that came to define 80s pop music, Gabriel belies some of his inherited sense of innovation with New Blood (his father, Ralph, was an electrical engineer and inventor). That's not to say it lacks invention, it's just so tempting to think you're listening to an album of remixes. Orchestral remixes.

That said, as a long-term fan, I am bound to like the new version of San Jacinto, which is painted from a bigger palette and on a bigger canvas than the original on Peter Gabriel 4 (or Security as it was later renamed to help bewildered souls unable to distinguish between the first four albums, all named Peter Gabriel).

Equally, I'm intrigued by the new approach to In Your Eyes. In it's original form, a lively, African-rhythmed love song which has provided the keynote to many a new relationship; on New Blood, it is transformed into something sparse, choral and bewitchingly cold. Likewise, Mercy Street, Gabriel's tribute to the author Anne Rice, which is more open than the claustrophobic original on So. Others work less well: Digging In The Dirt, written as a therapeutic, analytic and somewhat angry conclusion to Gabriel's failed first marriage, loses the sinister tone with the addition of an orchestra, while Rhythm Of The Heat loses its unique - for 1982 - world music undercurrent, the African drumming that has since been used by many a lazy documentary director struggling to find an 'ethnic' soundtrack.

New Blood will be a fan's favourite for sure: we'll tolerate the mild disappointments and rave over the triumphs, as we're supposed to. We would just hope, however, that Gabriel will now return to the studio and make a 'proper' album, even if it takes another 10 years as all his others do.

Walt Disney or Willy Wonka?

One of the many memorable moments in Steven Spielberg's E.T. prequel-of-sorts, Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, is the sight of Roy Neary, Richard Dreyfuss' character, going mad and sculpting a flat-topped mountain out of mashed potato.

This was, we later found out, because aliens had planted the image of the very real Devil’s Tower in Wyoming in Neary's mind and were calling him - and others – to assemble there.

I was thinking about this last Tuesday, just as the media - and I don't just mean the technology media - were getting excited about Apple's latest press event. Not knowing why (though they presumed it was the launch of the iPhone 5) they dutifully assembled at Apple's very own Devil's Tower, 1 Infinite Loop in Cupertino, California.

In the end there was no close encounter with anything other than a housekeeping update on what has made Apple the second-largest private company in the world (i.e. "We've sold lots of stuff, and Android is pants"), and that the iPhone 4 was to get a faster chip, a better camera and be offered as the iPhone 4S. Motoring experts will know that this approach is akin to putting 'Go Faster' trim on an existing Ford Fiesta to sell off inventory prior to a new model being launched.

The task of landing this non-news fell to Tim Cook, the company's new CEO who had, during Steve Jobs' various periods of medical leave, proven himself to be a steady-as-a-rock understudy. Since Jobs stepped down as CEO in August, Cook had eased the concerns of investors and employees alike. So, with the Apple obsessives entering overdrive and tech news websites offering Tweet-by-Tweet "live" coverage from the event - as if this made any more difference than more considered, consolidated coverage later - Cook, supported by assorted Apple upper managers, sought to make his mark.

The verdict was that, while Cook may be a worthy CEO, he is no Steve Jobs. 48 hours later, the copious outpouring of tribute and comment from journalists, peers and consumers at the news that Jobs was dead, underlined the point that there will probably only ever be one Steve Jobs.

Whatever your view about him, whether you saw him as the Da Vinci, the Walt Disney or even the Willy Wonka of his time, there is no doubt that the almost hard to take in explosion of media coverage marking his demise spoke volumes. People have likened it to the deaths of John Lennon or Elvis Presley. Actually, its volume has probably been closer to that which followed Princess Diana's passing. She was 'The People's Princess', but Steve Jobs was, we all know, just a Silicon Valley entrepreneur who, like many others in the Palo Alto and Mountain View districts, co-founded a computer business in a garage. Less than 30 years later - with most of the growth within the last decade - he'd turned it into a global corporate behemoth, not just a technology giant.

I'll spare the whole chronology - you'll have read it anyway in great detail since Thursday. The bottom line is that Jobs' ascendance to world-revered icon - credited with single-handedly transforming global culture through little more than silicon, software, good industrial design and an uncanny knack of knowing how to make existing technology both easier to use and desirable to those who'd otherwise be indifferent towards it - took just 13 years.

The original iMac presented the foundation: it challenged the idea of what a home computer not only should look like, but what it should do, and even who should own it. Add in easy-to-use software for otherwise professional applications like movie editing, add in connectivity for digital cameras, and the digital lifestyle for the non-geek was ready to go. Think back to that moment in 1998 when the iMac appeared in all its fruity-coloured versions, and then speed through the arrival of the iPod, iTunes, more iMacs, iPod Nano, iPod Shuffle, iPhone, iPod Touch, iPad to the iPhone 4S, and you see something which can only be regarded as breathtaking. This is the same company which, in 1998, was regarded as a niche player with a tiny market share.

Apple's progress, from once bankruptcy-threatened cult-in-waiting, to the world's eighth most-admired brand and a company with more cash than the US Federal Reserve can only be credited to one man. No matter what contribution Jonathan Ive's brilliant design has made, Phil Schiller's smart marketing or Tim Cook's solid operational management as COO, not to mention the tireless involvement of countless engineers and anonymous assembly-line workers in China, Apple today - the phenomenon that Apple has become - is down to Steve Jobs.

His instinct, as to what you and I as consumers would want, was the key. There were PCs before the iMac; there were MP3 players before the iPod; there were tablet devices before the iPad; there was music management software before iTunes. Jobs made them both attractive, aspirational and desirable, but also made them indispensable. Even when he apparently reluctantly opened iTunes up to the Windows PC, he was - like extra-terrestrial telepathy - planting the seeds that would hold consumers dependent on the Apple brand for their next generation of MP3 players and, eventually, mobile phone.

We all know the iPhone is lousy as a phone, but we make allowances because it does so much more which works well, which makes it satisfying to use - even fun - and has clearly been thought through, inside and out, inception to consumption. The Apple environment is a clever one - the blog post I write as a note on my iPhone over breakfast, is enhanced on the iPad while I fly across the Atlantic, to be rendered and published using the MacBook on arrival at the hotel. Pity me for having shelled out three times for the same functionality, but in having the vision and shear bloody mindedness to insist he knew what we'd happily fork out for in the pursuit of our digital lifestyles, Steve Jobs was an unparalleled genius - magician, vaudeville showman and street corner dime-bag pusher rolled into one.

What happens next for Apple is down to others. It's Jobs' legacy for them to enhance, maintain or ruin. If nothing else, the 13 years since he unveiled that very first iMac have been remarkable, breathless and deliciously good fun to have witnessed and, let's face it, bought into. At a premium, of course.

This was, we later found out, because aliens had planted the image of the very real Devil’s Tower in Wyoming in Neary's mind and were calling him - and others – to assemble there.

I was thinking about this last Tuesday, just as the media - and I don't just mean the technology media - were getting excited about Apple's latest press event. Not knowing why (though they presumed it was the launch of the iPhone 5) they dutifully assembled at Apple's very own Devil's Tower, 1 Infinite Loop in Cupertino, California.

In the end there was no close encounter with anything other than a housekeeping update on what has made Apple the second-largest private company in the world (i.e. "We've sold lots of stuff, and Android is pants"), and that the iPhone 4 was to get a faster chip, a better camera and be offered as the iPhone 4S. Motoring experts will know that this approach is akin to putting 'Go Faster' trim on an existing Ford Fiesta to sell off inventory prior to a new model being launched.

The task of landing this non-news fell to Tim Cook, the company's new CEO who had, during Steve Jobs' various periods of medical leave, proven himself to be a steady-as-a-rock understudy. Since Jobs stepped down as CEO in August, Cook had eased the concerns of investors and employees alike. So, with the Apple obsessives entering overdrive and tech news websites offering Tweet-by-Tweet "live" coverage from the event - as if this made any more difference than more considered, consolidated coverage later - Cook, supported by assorted Apple upper managers, sought to make his mark.

The verdict was that, while Cook may be a worthy CEO, he is no Steve Jobs. 48 hours later, the copious outpouring of tribute and comment from journalists, peers and consumers at the news that Jobs was dead, underlined the point that there will probably only ever be one Steve Jobs.

Whatever your view about him, whether you saw him as the Da Vinci, the Walt Disney or even the Willy Wonka of his time, there is no doubt that the almost hard to take in explosion of media coverage marking his demise spoke volumes. People have likened it to the deaths of John Lennon or Elvis Presley. Actually, its volume has probably been closer to that which followed Princess Diana's passing. She was 'The People's Princess', but Steve Jobs was, we all know, just a Silicon Valley entrepreneur who, like many others in the Palo Alto and Mountain View districts, co-founded a computer business in a garage. Less than 30 years later - with most of the growth within the last decade - he'd turned it into a global corporate behemoth, not just a technology giant.

I'll spare the whole chronology - you'll have read it anyway in great detail since Thursday. The bottom line is that Jobs' ascendance to world-revered icon - credited with single-handedly transforming global culture through little more than silicon, software, good industrial design and an uncanny knack of knowing how to make existing technology both easier to use and desirable to those who'd otherwise be indifferent towards it - took just 13 years.

The original iMac presented the foundation: it challenged the idea of what a home computer not only should look like, but what it should do, and even who should own it. Add in easy-to-use software for otherwise professional applications like movie editing, add in connectivity for digital cameras, and the digital lifestyle for the non-geek was ready to go. Think back to that moment in 1998 when the iMac appeared in all its fruity-coloured versions, and then speed through the arrival of the iPod, iTunes, more iMacs, iPod Nano, iPod Shuffle, iPhone, iPod Touch, iPad to the iPhone 4S, and you see something which can only be regarded as breathtaking. This is the same company which, in 1998, was regarded as a niche player with a tiny market share.

Apple's progress, from once bankruptcy-threatened cult-in-waiting, to the world's eighth most-admired brand and a company with more cash than the US Federal Reserve can only be credited to one man. No matter what contribution Jonathan Ive's brilliant design has made, Phil Schiller's smart marketing or Tim Cook's solid operational management as COO, not to mention the tireless involvement of countless engineers and anonymous assembly-line workers in China, Apple today - the phenomenon that Apple has become - is down to Steve Jobs.

His instinct, as to what you and I as consumers would want, was the key. There were PCs before the iMac; there were MP3 players before the iPod; there were tablet devices before the iPad; there was music management software before iTunes. Jobs made them both attractive, aspirational and desirable, but also made them indispensable. Even when he apparently reluctantly opened iTunes up to the Windows PC, he was - like extra-terrestrial telepathy - planting the seeds that would hold consumers dependent on the Apple brand for their next generation of MP3 players and, eventually, mobile phone.

We all know the iPhone is lousy as a phone, but we make allowances because it does so much more which works well, which makes it satisfying to use - even fun - and has clearly been thought through, inside and out, inception to consumption. The Apple environment is a clever one - the blog post I write as a note on my iPhone over breakfast, is enhanced on the iPad while I fly across the Atlantic, to be rendered and published using the MacBook on arrival at the hotel. Pity me for having shelled out three times for the same functionality, but in having the vision and shear bloody mindedness to insist he knew what we'd happily fork out for in the pursuit of our digital lifestyles, Steve Jobs was an unparalleled genius - magician, vaudeville showman and street corner dime-bag pusher rolled into one.

What happens next for Apple is down to others. It's Jobs' legacy for them to enhance, maintain or ruin. If nothing else, the 13 years since he unveiled that very first iMac have been remarkable, breathless and deliciously good fun to have witnessed and, let's face it, bought into. At a premium, of course.

Steve Jobs

1955-2011

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)